![]()

Art Director × Art Setting

Junichi Higashi × Yohei Kodama (Part 1)

In anime, the task of broadening the worldview and instilling the locations with a sense of presence and conviction is entrusted to "background art." In "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM THE ORIGIN" (hereafter referred to as "THE ORIGIN"), the background art had to be perfect in order to create a new depiction of the Universal Century worldview. This time around, we spoke in two parts with Art Director Junichi Higashi and Art Setting Designer Yohei Kodama of the background art production company Studio Easter, which handled the overall art on "THE ORIGIN".

Kodama: An art setting designer's job is to create art-related designs before the point where they appear onscreen.

Kodama: An art setting designer's job is to create art-related designs before the point where they appear onscreen.

Higashi: Art setting is something like stage set design. Please think of it as the blueprints for the worldview. If you think of the art boards which the art director paints as the atmosphere of the worldview, I think you'll understand the difference. The art boards create the worldview's look, mood, and flavor, so the job of art setting is like that of an architect who makes stage sets. Thus, a designer in the world of art is an art designer, and you wouldn't refer to the background artist as a designer. It's somewhat close to an art director. The artist's job is to take the line drawings created by the art designer and decide what atmosphere of the world to color them with. It's easy to understand the work of a background artist as being the use of color.

Kodama: The setting work itself is intended for both the animators and the people painting the art boards, and it has to incorporate explanation of the worldview into the design. So it's a combination of jobs. Within that, we have to turn the artwork of the famed "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM" into new setting. So there are some things we can't just do as we please, and other things that weren't described in too much detail in the original work which we have to supplement. The work is a mix of those things. We try to skillfully add some originality within those parameters, and in my case my method is to be very precise, producing modern detailing while also retaining what's good about the old versions. That's how we put together the designs.

Kodama: The setting work itself is intended for both the animators and the people painting the art boards, and it has to incorporate explanation of the worldview into the design. So it's a combination of jobs. Within that, we have to turn the artwork of the famed "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM" into new setting. So there are some things we can't just do as we please, and other things that weren't described in too much detail in the original work which we have to supplement. The work is a mix of those things. We try to skillfully add some originality within those parameters, and in my case my method is to be very precise, producing modern detailing while also retaining what's good about the old versions. That's how we put together the designs.

Kodama: With regards to the art setting, Mr. Yasuhiko himself made requests saying, "This is how I see it." For example, he was, like, "Gihren is this kind of person, so let's have his room be like so." Since this was a special request from the manga author and general director, it was important to push it as a crucial point to make it a reality. Sometimes the requests themselves were tough, but Mr. Yasuhiko himself had a detailed image of how he would like us to draw it, so right there he would draw a smooth, simple drawing, like, "From this angle, like this." When he explained it concretely like that, it was easy to understand. On the other hand, when I draw things that Mr. Yasuhiko himself wasn't satisfied with when he drew the comic, there's no concrete guideline, so I simply have to search out the answer myself, and that's hard. In such cases, I prepare a few different versions so I can determine in which direction I should proceed.

Higashi: With regards to background art, I've mostly gone digital. That said, the difference between digital and analog is really not that great. Basically, there's no change in the painting of the pictures. The way work flows on TV series and industry work now, if you don't use digital for the backgrounds, then you can't keep up with the work. Because there are lots of things you can't keep up with in analog when you're trying to meet the director's production requests. In that sense, using digital has become mainstream in the industry. On the other hand, in things like a big-budget theatrical feature, when things are painted in careful detail, they produce depth. That's merely a question of what works best, so some painting by hand still remains. In any event, pictures painted digitally doesn't need to be scanned as material for filming, but in the case of a hand-painted piece, unless you scan it in and turn it into digital data, then it can't be used in modern anime. For these kinds of time-saving reasons as well, digital is now predominant.

Kodama: With the art setting as well, as I said, I haven't gone digital. But I sometimes need to create orthographic views on the assumption they will be turned into 3D, and I consciously add parts that will become visible when the angle changes. Higashi: On "THE ORIGIN," Mr. Yasuhiko is at the top, so he's making it an old school way, in a good sense. Orthodox production methods that have been around for ages. When working with relatively young directors these days, their instructions are very detailed and they make incredibly pinpoint requests. The trend now is that it's not the scene, but the way the background is shown in each shot itself that's decided in great detail, from the level of lighting to the colors. In many instances, it's not really a creative job. "THE ORIGIN" is looser, and more is left in our hands, and suggestions from us go through more easily. It's easy for us to get them to consider our intentions, so it's easier to do. In Sunrise projects such as "THE ORIGIN," they tend to be more open to the opinions of the art director and designers. So it's worthwhile working on it.

Higashi: On "THE ORIGIN," Mr. Yasuhiko is at the top, so he's making it an old school way, in a good sense. Orthodox production methods that have been around for ages. When working with relatively young directors these days, their instructions are very detailed and they make incredibly pinpoint requests. The trend now is that it's not the scene, but the way the background is shown in each shot itself that's decided in great detail, from the level of lighting to the colors. In many instances, it's not really a creative job. "THE ORIGIN" is looser, and more is left in our hands, and suggestions from us go through more easily. It's easy for us to get them to consider our intentions, so it's easier to do. In Sunrise projects such as "THE ORIGIN," they tend to be more open to the opinions of the art director and designers. So it's worthwhile working on it.

Kodama: We clearly sense the temperaments of the creators. It's a company that respects us. In that sense, "THE ORIGIN" is a very easy job to work on.

- First of all, please tell us what the jobs of art director and art setting designer entail.

Higashi: The art director's job is to reproduce the story's worldview onscreen, according to the intentions of the general director and the episode directors. Basically, we often have more back-and-forth with the director of each episode than with the general director, so even if each episode has a different director, it's also the responsibility of the art director to find a balance so that the overall tone won't be inconsistent.  Kodama: An art setting designer's job is to create art-related designs before the point where they appear onscreen.

Kodama: An art setting designer's job is to create art-related designs before the point where they appear onscreen.Higashi: Art setting is something like stage set design. Please think of it as the blueprints for the worldview. If you think of the art boards which the art director paints as the atmosphere of the worldview, I think you'll understand the difference. The art boards create the worldview's look, mood, and flavor, so the job of art setting is like that of an architect who makes stage sets. Thus, a designer in the world of art is an art designer, and you wouldn't refer to the background artist as a designer. It's somewhat close to an art director. The artist's job is to take the line drawings created by the art designer and decide what atmosphere of the world to color them with. It's easy to understand the work of a background artist as being the use of color.

- In anime production there is a "color designer" who decides the colors for the characters and mecha. Does the background artist decide the colors for the worldview?

Higashi: That's right. Art setting and background art are both called "art," but the difference is generally hard to understand. General familiarity with animation is very high these days, and there are lots of die-hards who closely follow the background art, so I feel like the expectations and importance placed on the backgrounds by directors have also grown over these past ten years. Thus, at present some attention is being paid to that difference, more or less. At the same time the expectations for background art, including the art setting design within the work, as well as the director's feelings, have become much greater. So in that sense I'm thankful, but it's also become quite difficult.

- Regarding the background art, in terms of work flow, at what stage do you become involved with the production?

Higashi: Normally, at the stage that planning on the project commences, there's an initial sounding out about art, backgrounds, and setting. At that stage, we confirm the story's worldview, and if it seems like we're up to it, we take on the task and start work at that point. In terms of the work itself, we talk with the general director and episode directors about the worldview and overall vision, and then we start with the art setting. As those tasks progress to a certain point, the scripts are completed, and we now proceed to create art boards to figure out the world of color. After that, when the storyboards are produced, we then plan for preparations to make even more detailed backgrounds.

- Was the amount of background art greater on "THE ORIGIN" than on other projects?

Higashi: "THE ORIGIN" is technically an OVA, but it's also intended for special theatrical screenings as well, so it's a unique project. In that sense, there was quite a volume of work compared to an ordinary OVA. In terms of content, too, it was necessary to draw various locations, and there were many variations of scenes, so it certainly was quite an involving project.

- Another aspect is that you had to reproduce the original "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM" in a modern way. What would you say you had to pay attention to with art setting in that respect?

Kodama: The setting work itself is intended for both the animators and the people painting the art boards, and it has to incorporate explanation of the worldview into the design. So it's a combination of jobs. Within that, we have to turn the artwork of the famed "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM" into new setting. So there are some things we can't just do as we please, and other things that weren't described in too much detail in the original work which we have to supplement. The work is a mix of those things. We try to skillfully add some originality within those parameters, and in my case my method is to be very precise, producing modern detailing while also retaining what's good about the old versions. That's how we put together the designs.

Kodama: The setting work itself is intended for both the animators and the people painting the art boards, and it has to incorporate explanation of the worldview into the design. So it's a combination of jobs. Within that, we have to turn the artwork of the famed "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM" into new setting. So there are some things we can't just do as we please, and other things that weren't described in too much detail in the original work which we have to supplement. The work is a mix of those things. We try to skillfully add some originality within those parameters, and in my case my method is to be very precise, producing modern detailing while also retaining what's good about the old versions. That's how we put together the designs.

- In concrete terms, what was the work process like?

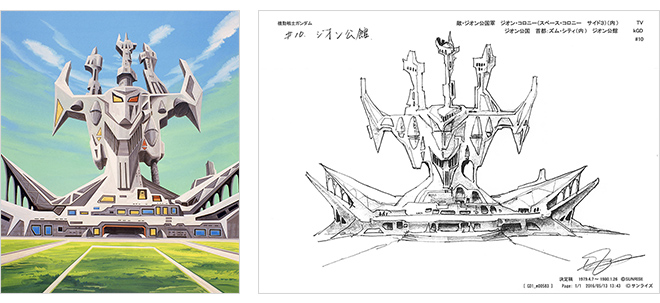

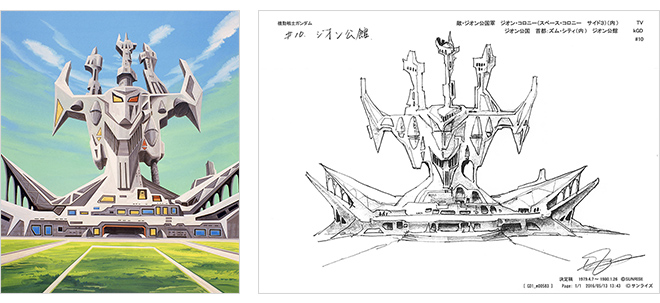

Kodama: I myself place the most importance on "concept design," or in other words, "form with meaning." So even if I'm redoing an existing design, I obsess about that. The royal residence in Zum City, which first appears in Episode 5, is a good example of that. The original version where the Zabi family lives is impressive in itself. It's a building that has the form of a demonic face, like it symbolizes evil people. It's a building design that everyone knows well. And specifically because of that, I mustn't do anything to really upset that unique form. But I wracked my brains about how to express it in a modern way. Then I thought, first of all, "What meaning should I attach to that face-like form?" And I considered that concept. Reading the original manga deeply, I found Degwin's line: "It became a demon. Deikun's resentment became a devil and he was possessed by it." I took the shape of the building to be a manifestation of that Spacenoid resentment towards the Earth. I put that together with a fusion of a multifaceted formal and sculptural form of building called "Steiner buildings," which were advocated by a man named Rudolf Steiner, and the thinking behind ecclesiastical architecture. That was the direction I went in with the concept. To make that concept understood, I included text and presented it in this concept design form to Mr. Yasuhiko, and tried to get him to understand my thinking and vision. As a result, Mr. Yasuhiko was also able to understand the concept, and I was able to complete the new design. To plan it logically without changing the form of the royal residence, and to present the modern version in the right way, was truly difficult. So that's the process. We don't simply update the designs so they're modernized for "THE ORIGIN." We reinvestigate the elements of the concept and then tackle the art design.

【Translation】

I think everyone who takes one look at the Zabi residence can sense its ominousness, but I've replaced that ominous point with flames in my design. The thinker Kierkegaard had the philosophical concept of "ressentiment." It's a word that indicates a grudge or animosity, and it's a concept that Nietzsche also quoted. There's the literary expression "the flames of ressentiment," but it's used to mean the building up of frustration that the weak feel against the strong. In the manga, there's a line Degwin says to Kycilia, which is: "It became a demon. Deikun's resentment became a devil and he was possessed by it." I saw the place of Deikun's resentment as being those "flames of ressentiment" I mentioned before, and I crossed that with the ominousness of the Nakamura design for the Zabi residence. In refreshing the design, I consciously tried to make the overall form take on the flame concept. I made the three tower-like projections at the top look like torches burning in fury. The above is an overall explanation of the concept, but I refined the details into the almost sculptural structure that Mr. Yasuhiko spoke of, and made it into a place which has more of an atmosphere that people actually live there by referencing Steiner buildings and old Soviet avant-garde reliefs.

I think everyone who takes one look at the Zabi residence can sense its ominousness, but I've replaced that ominous point with flames in my design. The thinker Kierkegaard had the philosophical concept of "ressentiment." It's a word that indicates a grudge or animosity, and it's a concept that Nietzsche also quoted. There's the literary expression "the flames of ressentiment," but it's used to mean the building up of frustration that the weak feel against the strong. In the manga, there's a line Degwin says to Kycilia, which is: "It became a demon. Deikun's resentment became a devil and he was possessed by it." I saw the place of Deikun's resentment as being those "flames of ressentiment" I mentioned before, and I crossed that with the ominousness of the Nakamura design for the Zabi residence. In refreshing the design, I consciously tried to make the overall form take on the flame concept. I made the three tower-like projections at the top look like torches burning in fury. The above is an overall explanation of the concept, but I refined the details into the almost sculptural structure that Mr. Yasuhiko spoke of, and made it into a place which has more of an atmosphere that people actually live there by referencing Steiner buildings and old Soviet avant-garde reliefs.

- What kind of communication do you have with General Director Yoshikazu Yasuhiko?

Higashi: With regards to art and background, we get explanations from Mr. Yasuhiko about the vision for the new scenes in each episode. On the other hand, we don't talk about the overall vision of the project. We've been able to work on various Gundam projects, starting with "MOBILE SUIT Z GUNDAM," and including "MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM 0083" and "MOBILE FIGHTER G GUNDAM." Maybe for that reason, he feels we have a shared understanding of the Gundam world, so we didn't get any direct explanations about that.Kodama: With regards to the art setting, Mr. Yasuhiko himself made requests saying, "This is how I see it." For example, he was, like, "Gihren is this kind of person, so let's have his room be like so." Since this was a special request from the manga author and general director, it was important to push it as a crucial point to make it a reality. Sometimes the requests themselves were tough, but Mr. Yasuhiko himself had a detailed image of how he would like us to draw it, so right there he would draw a smooth, simple drawing, like, "From this angle, like this." When he explained it concretely like that, it was easy to understand. On the other hand, when I draw things that Mr. Yasuhiko himself wasn't satisfied with when he drew the comic, there's no concrete guideline, so I simply have to search out the answer myself, and that's hard. In such cases, I prepare a few different versions so I can determine in which direction I should proceed.

- Are aspects of the art production becoming digital?

Kodama: With regards to art setting, I haven't gone digital. Of course you can also design in 3D, but it takes a lot of time, and drawing by hand is faster. When designing, I often first make a rough outline in pencil and then gradually give it more shape and detail, so I'm more used to drawing by hand without using a PC.Higashi: With regards to background art, I've mostly gone digital. That said, the difference between digital and analog is really not that great. Basically, there's no change in the painting of the pictures. The way work flows on TV series and industry work now, if you don't use digital for the backgrounds, then you can't keep up with the work. Because there are lots of things you can't keep up with in analog when you're trying to meet the director's production requests. In that sense, using digital has become mainstream in the industry. On the other hand, in things like a big-budget theatrical feature, when things are painted in careful detail, they produce depth. That's merely a question of what works best, so some painting by hand still remains. In any event, pictures painted digitally doesn't need to be scanned as material for filming, but in the case of a hand-painted piece, unless you scan it in and turn it into digital data, then it can't be used in modern anime. For these kinds of time-saving reasons as well, digital is now predominant.

- "THE ORIGIN" has many scenes which combine background art and 3D modeling. Did that also change the process?

Higashi: Right now, speaking in terms of the art industry, it's like a second revolutionary era. The first revolution was when we started using Photoshop software, and creating backgrounds for anime became more efficient. Now the second revolution is arriving, and the background artists are using 3D software. By using 3D, the work process gains greater efficiency, and it also helps with the production. For example, in a school classroom scene where you have a troublesome arrangement of desks and chairs, or a sci-fi project where the scenes are full of fine, curved lines, it's hard to draw finely detailed layouts. But if you put those things together in 3D, it's easy to create the layouts. In the past, background art just meant adding color to the completed art setting, but now we're in an era where we assist the production and the animators.

- The boundaries of what your work entails must also be changing too, right?

Higashi: That's right. With regards to photography and 3DCG, until now, labor was precisely divided. But now we're all using software, so we're in an era where we can do anything. There's an issue of technical proficiency, but where that isn't a problem – for example, it's not like our background art production company can't study 3D software and After Effects – by using the same software, tasks which were separate become linked. We're now in an age where that's starting to become the situation. I'm interested to see how that's going to evolve going forward.

- One flow like that is the battle scene at the Earth Federation Forces barracks in Episode 3, where the backgrounds are depicted in 3DCG. Were you involved with that?

Higashi: That was a collaboration with Sunrise's D.I.D. Studio. Originally, it may have been okay for D.I.D. to do it on their own, but then they requested us, and we accepted it saying we would animate the backgrounds. This is another example in which previously separated operations are linked together. If you have the foundation of being able to use the software in place, many new possibilities arise. We took on D.I.D.'s work, and with our art team, we can process some work that the photography people typically do. That's how it's gone.Kodama: With the art setting as well, as I said, I haven't gone digital. But I sometimes need to create orthographic views on the assumption they will be turned into 3D, and I consciously add parts that will become visible when the angle changes.

- What are your thoughts on working on the art for "THE ORIGIN"?

Higashi: On "THE ORIGIN," Mr. Yasuhiko is at the top, so he's making it an old school way, in a good sense. Orthodox production methods that have been around for ages. When working with relatively young directors these days, their instructions are very detailed and they make incredibly pinpoint requests. The trend now is that it's not the scene, but the way the background is shown in each shot itself that's decided in great detail, from the level of lighting to the colors. In many instances, it's not really a creative job. "THE ORIGIN" is looser, and more is left in our hands, and suggestions from us go through more easily. It's easy for us to get them to consider our intentions, so it's easier to do. In Sunrise projects such as "THE ORIGIN," they tend to be more open to the opinions of the art director and designers. So it's worthwhile working on it.

Higashi: On "THE ORIGIN," Mr. Yasuhiko is at the top, so he's making it an old school way, in a good sense. Orthodox production methods that have been around for ages. When working with relatively young directors these days, their instructions are very detailed and they make incredibly pinpoint requests. The trend now is that it's not the scene, but the way the background is shown in each shot itself that's decided in great detail, from the level of lighting to the colors. In many instances, it's not really a creative job. "THE ORIGIN" is looser, and more is left in our hands, and suggestions from us go through more easily. It's easy for us to get them to consider our intentions, so it's easier to do. In Sunrise projects such as "THE ORIGIN," they tend to be more open to the opinions of the art director and designers. So it's worthwhile working on it.Kodama: We clearly sense the temperaments of the creators. It's a company that respects us. In that sense, "THE ORIGIN" is a very easy job to work on.

- Next time, we'll talk more closely about the content of "THE ORIGIN" itself, and we'd like to know more about the details of the background art and on which aspects you're more focused.